The Role of the Prison Guards Union in California’s Troubled Prison System

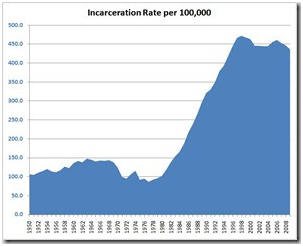

Jailing is big business. California spends approximately $9 billion a year on its correctional system, and hosts one in seven of the nation’s prisoners. It has the largest prison population of any state. The number of correctional facilities, the amount of compensation for their unionized staffs, and the total cost of incarcerating a prisoner in the state—$44,563 a year—have exploded over the past 30 years. Over that same period, the quality of the state’s prison system declined precipitously. From the 1940s to the 1960s, California’s correctional system was the envy of the nation: Its wardens held advanced degrees in social work and wrote groundbreaking studies on prisoner reform and reducing recidivism. “California was the model of good correctional management and inmate programming,” says Joan Petersilia in California’s Correctional Paradox of Excess and Deprivation, 37 Crime & Just. 207, 209 (2008), “and its practices profoundly influenced American corrections for over 30 years.” By the 1980s, however, California began radically reforming its prison system. An incarceration rate that had held to 100 to 150 per 100,000 Californians prior to 1980 spiked to over 450 by the year 2000. The prison population surged from less than 25,000 in 1980 to more than 168,000 in 2009. The state’s prison budget swelled to meet the needs of the more than six-fold population increase. Between 1980 and 2000, California built 23 new prisons. New guards were needed to staff the new facilities, increasing their number from approximately 5,600 to nearly 30,000 over the same period. Prior to construction, annual spending on the state’s correctional program amounted to about $675 million, or about 3% of California’s general fund. By 2008, spending topped $10 billion, and consumed almost 11.5% of the state’s general fund. It still wasn’t enough, however, since spending on rehabilitation was systematically excised from the state’s correctional policy at the same time in around 1980. As a result, according to the San Francisco Chronicle in 2002, California has the highest rate of recidivism in the nation: Before the mid-1970s, most sentences were indeterminate, meaning that most inmates could get off much earlier than their original sentence if they completed vocational or academic classes in addition to good behavior. The state replaced that system with one lacking an incentive for inmates to take classes or get counseling to help them prepare for life outside prison. Now, virtually everyone released from prison spends three years on parole. Most – about 71 percent – end up back in prison within 18 months – the nation’s highest recidivism rate and nearly double the average of all other states. According to data provided by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, in 1977, parolees who were returned to prison or convicted of new crimes accounted for just 10% of California’s prison population. The percentage topped 20 only once prior to 1980. In 2009, however, the number was an alarming 77%, having held firm between the high 60s and low 80s since 1986.

The growth of California’s incarceration system, and the decline of its quality, tracks the accession to power of the state’s prison guards union, the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (“CCPOA”). The CCPOA has played a significant role in advocating pro-incarceration policies and opposing pro-rehabilitative policies in California. In 1980, CCPOA’s 5,600 members earned about $21,000 a year and paid dues of about $35 a month. After the rapid expansion of the prison population beginning in the 1980s, CCPOA’s 33,000 members today earn approximately $73,000 and pay monthly dues of about $80. These dues raise approximately $23 million each year, of which the CCPOA allocates approximately $8 million to lobbying. As Ms. Petersilia explains, “The formula is simple: more prisoners lead to more prisons; more prisons require more guards; more guards means more dues-paying members and fund-raising capability; and fund-raising, of course, translates into political influence.”

The

CCPOA has used this political influence to advance a highly successful pro-incarceration agenda. Alexander Volokh writes in his article, Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, 66 Stanford Law Review 1197 (2008): many of [CCPOA’s] contributions are directly pro-incarceration. It gave over $100,000 to California’s Three Strikes initiative, Proposition 184 in 1994, making it the second-largest contributor. It gave at least $75,000 to the opponents of Proposition 36, the 2000 initiative that replaced incarceration with substance abuse treatment for certain nonviolent offenders. From 1998 to 2000 it gave over $120,000 to crime victims’ groups, who present a more sympathetic face to the public in their pro-incarceration advocacy. It spent over $1 million to help defeat Proposition 66, the 2004 initiative that would have limited the crimes that triggered a life sentence under the Three Strikes law. And in 2005, it killed Gov. Schwarzenegger’s plan to “reduce the prison population by as much as 20,000, mainly through a program that diverted parole violators into rehabilitation efforts: drug programs, halfway houses and home detention.” Ms. Petersilia further observes that “CCPOA-sponsored legislation was successful more than 80 percent of the time” during the

‘80s and ‘90s, including most notably California’s aggressive three-strikes initiative passed in 1984. Following the 2010 elections, one CCPOA lobbyist boasted “we should be able to develop a good contract with this governor given the fiscal times the state’s in, and we should have no trouble getting it ratified. We have such good relationships, and we were right in so many races, that we’ve got a lot of friends over there.” Thus, while the state’s pro-incarceration laws swell union membership and dues revenue, the CCPOA is able to successfully lobby for more generous compensation for their membership. As of July 2006, the average CCPOA correctional officer earned $73,248 a year—more than the average salary of an assistant professor with a PhD at the University of California ($60,000 per year in 2006). With overtime, it is not uncommon for California correctional officers to earn over $100,000 a year. A Los Angeles Times investigation found that 6,000 correctional officers earned more than $100,000 in 2006, with hundreds earning more than legislators and other state officials. Prison guards also enjoy pensions calculated using the favorable 3%-at-50 formula. An officer who retires at 50 takes as his pension a percentage of his last year’s salary equal to three times the number of years worked. (For example, an officer who retires at age 50 after 30 years on the job will receive 90% of his salary during retirement (3 x 30 years). More on this subject here.) Since the maximum retirement benefits are 90 percent, working past 30 years is basically working for free. Teachers, by contrast, receive a pension calculated as 2.5 percent of their salaries per year of employment at age 63. As CCPOA member Lt. Kevin Peters observed, the union’s successful pro-incarceration policy results in more and better opportunities for union members: You can get a job anywhere. This is a career. And with the upward mobility and rapid expansion of the department, there are opportunities for the people who are [already] correction staff, and opportunities for the general public to become correctional officers. We’ve gone from 12 institutions to 28 in 12 years, and with “Three Strikes” and the overcrowding we’re going to experience with that, we’re going to need to build at least three prisons a year for the next five years. Each one of those institutions will take approximately 1,000 employees. The facts observed over the past 40 years suggests the cycle described by Ms. Petersilia is basically accurate: higher incarceration leads to greater union influence, which in turn leads to still higher incarceration, and thus higher union membership, revenues, and political influence. Whatever the initial causes of California’s prison problems, the prison guards’ institutional pro-incarceration and anti-rehabilitation agenda has calcified a broken correctional system. Timeline of the CCPOA’s Influence in California’s Crime, Incarceration, and Rehabilitation Policies To provide an understanding the CCPOA’s objectives in and influence over California’s prison system, it may be helpful to recite a brief history of the prison system since the CCPOA’s inception over 50 years ago:

• 1957: California Correctional Officers Association (the predecessor to the CCPOA) is founded.

• 1972: In its initial decades, the CCOA largely backed conservative political measures. For example, in 1972 the CCOA backed Prop 17, which amended the California Constitution reinstating capital punishment following the California Supreme Court decision in People v. Anderson, holding the death penalty violated the state constitutional prohibition against “cruel or unusual punishment.”

• 1973: The CCOA reaches 3,200 members. It is still dwarfed by the 102,000 member California State Employees Association.

• 1976: California becomes the second state after Maine to abolish indeterminate sentencing, which had explicitly embraced rehabilitation as a correctional goal and tied a prisoner’s release date to his or her rehabilitative progress.

• 1978: Gov. Jerry Brown signs the Dills Act into law, giving public employees collective bargaining rights.

• 1980: California has 12 prisons. Prison guards make approximately $21,000 per year.

• 1980: Don Novey takes over as president of CCPOA; although no longer working in a prison, Novey continues to receive his $59,900 salary, in addition to his new $60,000 union chief salary.

• 1983: By the end of Jerry Brown’s term as governor, total prison population increases by 9,899, from 24,471 to 34,640.

• 1983: CCPOA successfully negotiates a 2.5% at 55 retirement package.

• 1984: CCPOA membership swells to 10,000.

• 1990: CCPOA contributes $1 million to Pete Wilson.

• 1990: The CCPOA contributes over $80,000 to an unknown opponent of Senator John Vasconcellos, D-Santa Clara, who led opposition to a prison-building bond as an assemblyman in 1990. The much more visible Vasconcellos only narrowly defeated the unknown CCPOA-backed candidate.

• 1991: By the end of George Deukmejian’s term as governor, total prison population explodes by 62,669, from 34,640 to 97,309. The Corrections’ share of the General Fund saw an 81% increase over the past 8 years.

• July 1993: The CCPOA is one of the top 10 state political campaign contributors with more than $1 million in contributions, substantially to Republican candidates, including a challenger to an assemblyman who had repeatedly called for slowing growth in prison operating budgets.

• 1992: Prison guards’ pay averages $45,000 per year.

• 1994: With the help of CCPOA’s $101,000 support, Californians passed Proposition 184, the nation’s toughest three-strikes law mandating 25-years-to-life sentences for most felony offenders with two previous serious convictions.

• 1995: States around the country spend more building prisons than colleges for the first time in history.

• 1998: Don Novey, president of the CCPOA, contributes $2.1 million to the Gray Davis campaign.

• 1998: The CCPOA donates a total of $5.3 million to legislative races, the Gray Davis campaign, and voter initiatives. It was the No. 1 donor to California legislative races at $1.9 million. It contributed $2.3 million into Davis’s campaign, placed television spots for Davis in the conservative Central Valley, and helped fund a bank of telephone callers before the election. The CCPOA contributed $3 million to Gray Davis during his term in office.

• 1998: Since approximately 1980, California tripled its number of prisons and increased its inmate population to nearly 160,000 at 33 prisons and 38 work camps.

• 1998: Gov. Pete Wilson, who receives $1.5 million in CCPOA contributions in 1998, vetoes pay raises for other state workers while CCPOA members obtain a 12% pay increase, bringing top pay from $46,200 to $50,820. State university instructors earn between $32,000 and $37,000. By the end of Pete Wilson’s term as governor in 1999, total prison population increased by 67,875, from 97,309 to an estimated 165,166.

• 1999: After the Legislature approves a bill to establish a $1 million pilot program to provide alternative sentencing for some nonviolent parole offenders—estimated to save taxpayers $600 million a year—the CCPOA opposes the bill. Governor Gray Davis then vetoes the bill. The CCPOA also persuades Gov. Davis to close three privately run prisons, even though they housed inmates at substantially lower costs than state-run facilities.

• 2000: The CCPOA contributes at least $75,000 to the opponents of Proposition 36, the 2000 initiative that replaced incarceration with substance abuse treatment for certain nonviolent offenders.

• 2002: CCPOA contributes $1 million to Gray Davis’s campaign. The CCPOA contributes $200,000 to defeat Assemblyman Phil Wyman in 2002, an advocate of private prisons. The CCPOA negotiates an increase to prison guards’ pay estimated between 28% and 37%, at a price tag of $500 million per year. Senior guards earn $52,700 a year, compared to $30,000 for a senior supervisor in Texas. The California Legislature approves $170 million in extra prison spending. In addition to granting correctional officers a major boost in pay, the labor pact permitted officers to call in sick without a doctor’s note confirming the illness. With the new policy in place, prison officers called in sick 500,000 more hours in 2002 than in 2001, a 27% increase. “Our overtime would have been below 2001, or real close, had it not been for that 500,000-hour increase,” said Wendy Still, the main budget analyst for the Department of Corrections. Corrections officers called in sick 27 percent more often last year than they did in 2001, for an additional 500,000 lost hours. More than a third of the overtime logged last year was to compensate for guards who called in sick, according to the Bureau of State Audits. The California Department of Finance requests $70 million to cover unexpected prison costs from 2001. In December, Gray Davis asks lawmakers for $10 billion in emergency cuts to other state programs.

• 2003: Gray Davis asks the Legislature to approve another $150 million for prison system’s budget. The CCPOA contributes $25,000 to Senate President Pro Tem John Burton, a San Francisco Democrat, three months after giving $12,000 to Senate Republican Leader Jim Brulte of Rancho Cucamonga. CCPOA members receive a 7% raise, pushing average annual take-home pay to $64,000. California’s prison budget is estimated at $5.2 billion.

• 2004: The CCPOA spends over $1 million to defeat Prop 66, the initiative that would have limited the crimes that triggered a life sentence under the Three Strikes law.

• 2005: The CCPOA defeats Governor Schwarzenegger’s plan to “reduce the prison population by as much as 20,000, mainly through a program that diverted parole violators into rehabilitation efforts: drug programs, halfway houses and home detention.” Spending on California’s penal system constitutes approximately 7% of the state’s general funds. CCPOA membership reaches 26,000.

• 2006: The average CCPOA correctional officer receives compensation worth $73,248 per year. Over 900 workers added $50,000 or more to their base salaries in overtime pay; over 1,600 officers’ total earnings topped $110,000. (Kathryne Tafolla Young, The Privatization of California Correctional Facilities: A Population-Based Approach, 18 Stan. L. & Pol’y Rev. 438, 441-42 (2007).)

• 2007: Following a 2007 ruling requiring the state to fix its prison overcrowding problem, the Legislature passes a $3.5 billion bond package to finance the construction of new prisons, yet four years later not a single new facility has been built.

• 2008: The CCPOA contributes $2 million to Jerry Brown’s gubernatorial campaign. The CCPOA contributes $1 million against Prop 5, a measure to reduce prison overcrowding by providing treatment rather than prison sentences for nonviolent drug users.

• 2011: Gov. Brown’s proposed Fiscal Year 2011-2012 budget funds the prison system $9.19 billion, nearly 7.2% of the entire state budget. It costs an average of $44,563 a year to house each of California’s approximately 158,000 inmates in a system at roughly 200% of capacity. The national average is $28,000.

By 2011, CCPOA members are among the most generously compensated public workers in the state, even while their union resists policy changes to bring prison overcrowding, recidivism, and costs under control. As observed by Rich Tatum, a 33-year prisons veteran and president of the California Correctional Supervisors Organization, “It does seem at times like the union is running the department.” John Irwin, a retired professor and commentator of California’s correctional system, worries that “the wardens don’t feel they have much control of what goes on. The cliques – mostly led by sergeants – at the prisons are very strong, and the union, of course, backs them up when they get into trouble.” That the CCPOA effectively wields so much governmental power explains how the misconduct of their members goes unchecked, and reported sexual assault, unreasonable use of tasers and pepper spray, hitting with flashlights and batons, punching and kicking, slurs and racial epithets, among others, go uninvestigated. According to the 138-page opinion in Madrid v. Gomez, 889 F. Supp. 1146 (N.D.Cal. 1995), “The court finds that supervision of the use of non-lethal force at Pelican Bay is strikingly deficient,” and “It is clear to the Court that while the IAD [Internal Affairs Division] goes through the necessary motions, it is invariably a counterfeit investigation pursued with one outcome in mind: to avoid finding officer misconduct as often as possible. As described below, not only are all presumptions in favor of the officer, but evidence is routinely strained, twisted or ignored to reach the desired result.” The court held that the prison guards and officials engaged in unnecessary infliction of pain and use of excessive force, and violated the Eighth Amendment, among other things. According to testimony in Madrid, from 1989 to 1994 officers in California’s state prisons shot and killed more than 30 inmates. By contrast, in all other state and federal prisons nationally only 6 inmates were killed in the same period-and 5 of those were shot while attempting to escape. Compounding this misconduct is the systemic lack of transparency preventing the public from knowing the full extent of the guards’ abuses. Union members, for example, employ a “code of silence” to squelch evidence of misconduct: Even if the CDC were more thorough in its investigation of officer misconduct, it would have to overcome the membership’s last line of defense-a widely accepted code of silence. In the Madrid case, Judge Henderson referred to the “undeniable presence of a ‘code of silence’ … designed to encourage prison employees to remain silent regarding the improper behavior of their fellow employees, particularly where excessive force has been alleged.” 889 F Supp at 1157. Novey, asked in the 1998 state Senate hearings if he would say such a code existed, replied, “I wouldn’t totally say that…. But I will attest that there are pockets [of the code], and our job’s to help weed out those pockets.” As the Madrid ruling chillingly observes, “Certainly, much has transpired at Pelican Bay California state prison of which the Court will never know.” Concurrent with the abuses described in Madrid, similar abuses were under investigation at Corcoran State Prison concerning guards using firearms to break up fist fights: The investigations at Corcoran State Prison eventually led to the federal indictment of eight officers for allegedly staging “blood sport” fights between inmates that occurred in the security housing unit in 1994. Before the trial, the CCPOA financed an infomercial in 1999 about the tough working conditions at Corcoran. Thomas E. Quinn, a private investigator in Fresno who produced a documentary video showing some of the fights, says the union’s infomercial showed “prison guards as neighbors, and prisoners as the scum of the earth.” Broadcast by local television stations prior to jury selection, the ad concluded with the tag line “Corcoran officers: They walk the toughest beat in the state.” Although prosecutors expressed concern about the ads to the trial judge, they didn’t attempt to stop the broad-casts. The jury eventually acquitted the eight guards of all charges. Immediately after the verdict, some jurors joined the defendants for an impromptu celebration.

Tame by comparison, the investigation earlier this year into prison guards who smuggled 10,000 cellphones to inmates in 2010—including one guard who obtained $150,000 through the illegal practice—hardly made a blip on anyone’s radar. Nor did this or the union’s many other abuses prevent it from successfully negotiating a vacation benefits package with Gov. Brown recently for, among other perks, eight weeks of vacation per year, additional time upon gaining seniority, and the right to cash out an unlimited amount of accrued vacation time upon retirement at final pay scale. Although the CCPOA insists the deal simply pays its members for the vacation days they were unable to take due to staffing shortages, the CCPOA itself is a significant contributor to the overcrowding and budgetary constraints that led to these shortages. As a result of the overcrowding and dismal conditions in California’s prisons, the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Plata recently ordered the state to reduce its prison population to 137.5% of design capacity by releasing approximately 37,000 prisoners. For California to comply with the high Court’s order, however, it must contend with a prison guards union at the height of its power. The state, on the one hand, must negotiate under a strict time table set by the Supreme Court while observing the constitutional protections of its prisoners and the interests of the public. The CCPOA, on the other hand, has the power to oust those elected officials who fail to put the union’s interests first. It’s a dangerous stand off, set in motion in part by Gov. Brown himself with the Dills Act in 1978. There is some poetic justice that, more than three decades later, it is Brown who must confront the powerful special interest he helped create. From Ordinary Times ~a group blog of politics, culture, and other various ramblings.

by Tim Kowal on June 6, 2011