The Score: Why Prisons Thrive Even When Budgets Shrink

Who says the government can’t do anything anymore?

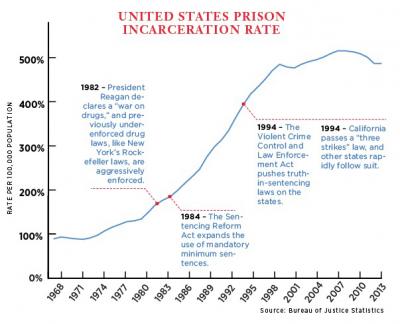

Even as Ronald Reagan argued that “government is the problem” throughout the 1980s, the state imprisoned twice the percentage of Americans previously incarcerated. As Bill Clinton declared “the era of big government” over in the 1990s, incarcerations skyrocketed to almost five times their rate in the 1970s—a rate that had been stable across the twentieth century. How did this happen?

Three actors determine daily incarceration rates: the police, prosecutors and judges. As shown in the graphic, a set of policies has increased the power of all three groups since 1982. They decide how often, and for what types of activities, people are arrested; how those arrests are turned into charges and convictions in a court of law; and how long the prison sentence is for each conviction.

The interactions between these three groups have given us what the National Research Council calls a “historically unprecedented and internationally unique” explosion in incarcerations since the 1980s. Under the “war on drugs,” aggressive policing drove up the percentage of those in state prisons for drug offenses from 6.4 percent in 1980 to 22 percent in 1990. More minor drug charges made it easier for prosecutors to push felony charges by citing a defendant’s prior record. These convictions triggered harsh sentences under new guidelines like California’s “three strikes” law, passed during the same period. The enforcement of these punitive new laws was, and remains, racist: according to the ACLU, black people are 3.73 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than whites, though they are equally likely to use. This, in turn, makes black people vulnerable to the rest of the criminal-justice system.

The media pay more attention to cops and judges, but mandatory minimums and “three strikes” laws transfer significant power to prosecutors, because so much depends on the initial charges filed. According to Fordham law professor John Pfaff, the rate at which prosecutors chose to pursue heavy felony charges increased dramatically in the 1990s, leading to more incarcerations. Recent high-profile cases like those of Marissa Alexander, Aaron Swartz and Cecily McMillan show prosecutors pressing the harshest charges and requesting long prison sentences, far in excess of any conceivable notion of justice. Prosecutors, as county-level employees, are also in the unique position to gain the electoral upside of looking “tough on crime” while passing off the costs of incarceration to the state. Given how little formal transparency prosecutors are subject to, perhaps (as activists have suggested for cops) they should be required to wear a body cam at all times.

Many will seek to make our system of incarceration more “fair.” But as Naomi Murakawa argues in her new book The First Civil Right, it’s precisely this response that feeds an unjust system resources and lends it legitimacy. Many of the initial sentencing acts were meant to provide fair, predictable guidelines, but prosecutors took advantage of them instead to rapidly escalate incarcerations. Money that President Clinton earmarked for “community policing” ended up being used by police for zero-tolerance programs like “stop-and-frisk.” As a result, we incarcerate too many people, for too long, and for the wrong reasons. The necessary agenda—from stopping the “war on drugs” to rejecting carceral force as our first response to social problems—requires not investing more in the existing criminal-justice system, but simply doing less.

Mike Konczal and Bryce Covert September 24, 2014